WashU’s chemistry chair shares a formula for scientific innovation — creating a culture where diversity thrives.

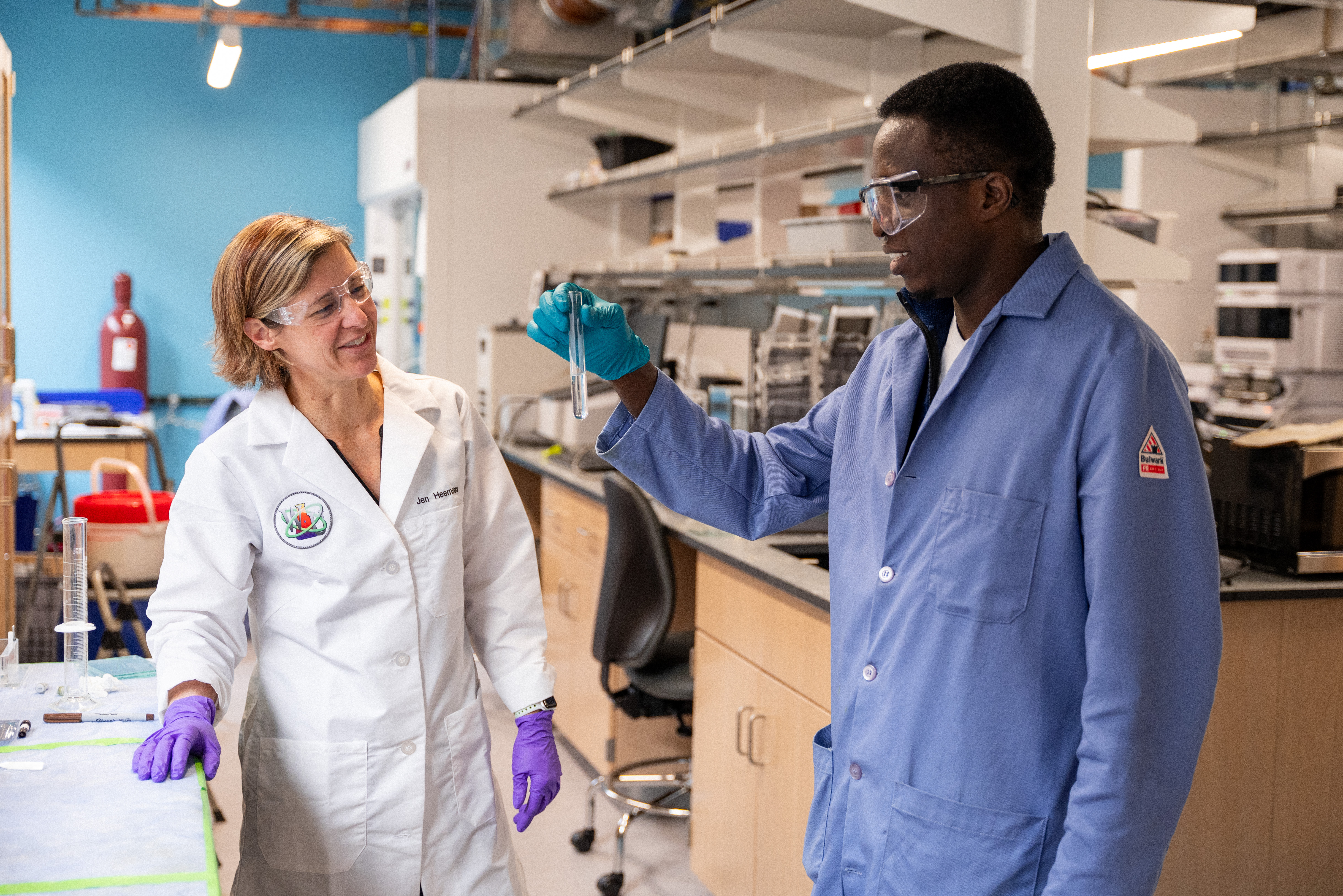

As the leader of one of WashU’s world-class science departments, it should come as no surprise that chemistry is an essential part of my job. But I’m not only talking about the study of chemical bonds. The 19 people in my lab — myself and 18 talented students and postdoctoral researchers — all have bonds of our own. We come from different parts of the world — Africa, Asia, Europe, the U.S. — and have different personalities, interests, and working styles. We also occasionally have disagreements and conflicts, which is exactly the way it should be.

We’re trying to answer novel questions and develop new technologies. No single person has all the knowledge or intuition needed for this research, which means we must work as a team. Simply put, science thrives in diversity.

When I talk about diversity, I’m always attuned to identities such as race, gender, nationality, sexuality, disability, and socioeconomic status. It’s vitally important to recognize the challenges faced by members of underrepresented groups. At the same time, diversity can take other forms that contribute to effective teams. These include diversity of life experiences, scientific backgrounds, and approaches to problem-solving. To propel cutting-edge research and innovation, we need everyone to contribute.

Embracing diversity goes beyond assembling a diverse team. As lab leaders, scholars, and members of a university community, we must also build a culture where everyone has a voice and a chance to thrive. This, in turn, takes leadership skills. For many, our formal training has focused exclusively on our academic discipline, but we can all embrace a few basic principles to eliminate barriers and create a healthy workplace culture.

One of the first steps is to recognize the playing field isn’t level for everyone. We live in a world where racism, sexism, and ableism make it more difficult for some groups of people to succeed than others. In a university setting, it can be easy for members of underrepresented groups to feel they don’t truly belong.

No single person can change an entire system, but there are things each of us can do to be more inclusive and welcoming. Think about how the people around you — in a classroom, office, or research lab — interact with each other. Does the dialogue aim to build up and encourage, or is it more likely to tear down and discourage? How open are people to learning from perspectives and life stories different from their own? Are people celebrating the unique aspects of others or exerting pressure to conform?

In our lab, feedback flows freely between all members of our group. The metrics of success in scientific research can often be unclear, leaving students and postdocs with the vague anxiety that they may not be meeting expectations or fitting in. My team knows where they stand and what they need to do to succeed. And their feedback is equally vital for me as a leader. I’m grateful that, over time, my group has candidly shared feedback on how I can be more effective in research discussions, more transparent in decision-making, and more supportive in individual mentoring interactions.

No single person has all the knowledge or intuition needed for this research, which means we must work as a team. Simply put, science thrives in diversity.

While I firmly believe in diversity as an ethical principle, it indisputably leads to better results. Every year, my lab gets together for a retreat where we set goals, brainstorm future research projects, and talk about lab policies. We have created a culture where diversity and (collegial) disagreements can thrive. This leads to better research ideas, which has increased our success at landing federal grants for our work.

I’m grateful to be at an institution that is at the forefront of creating change. That commitment is apparent in our institution-wide initiatives such as WashU Leads. On a personal level, I’ve had the opportunity to collaborate with university leaders to launch #MentorFirst. These groups, based on a nationwide initiative I co-founded, bring together small clusters of faculty (including me!) to discuss the experiences and challenges of leading a research group and to learn about effective, inclusive mentoring practices.

No mentor or researcher is perfect. We make mistakes. We run experiments that don’t work. We pursue avenues of inquiry that lead to dead ends. But we’ll always be stronger — and our research will be better — when we work together and create environments where everyone can thrive.

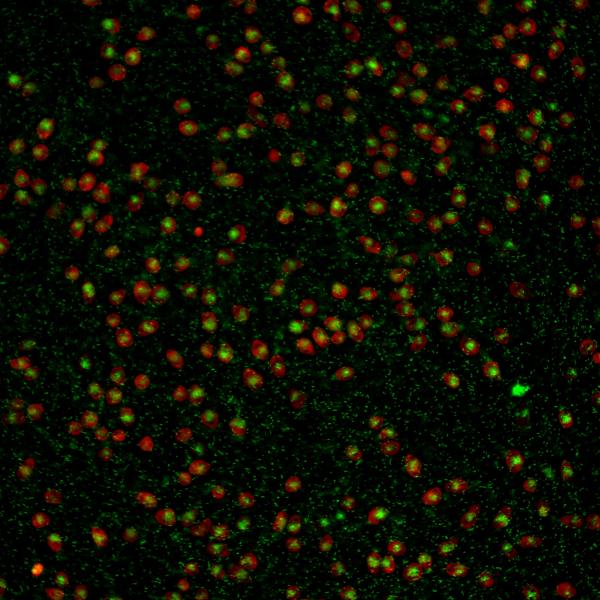

Jen Heemstra is the Charles Allen Thomas Professor of Chemistry and chair of the Department of Chemistry. Her lab focuses on harnessing the molecular recognition and self-assembly properties of nucleic acids and proteins for applications in biosensing and bioimaging. She is the author of a forthcoming book offering guidance for science lab leaders.